|

|

Francis “Mac” McKernon

Chief Radio Technician, USS Corry (DD-463)

I served aboard the USS

Corry from early January 1943 until June 6, 1944. At Normandy, I was a

27-year-old chief petty officer. As Chief Radio Technician on the Corry, I was in

charge of all radar, sonar, and radio operations and repair for the entire

ship. The Corry's signalmen also reported to me, as did

communications yeomen who performed clerical duties for our department. In

all, I supervised nearly 50 men aboard ship.

The Corry was the destroyer that led the Normandy invasion. Shortly before D-Day, as plans were being finalized, when I heard our officers saying, “The invasion is on, and we're going to lead it,” I asked them how we had earned such an honor. They said that we were given this honor because our gunners had hit every one of their targets and achieved the highest score when shooting at mock villages during the pre-invasion exercises in northern Britain.

With the Germans trying to fend off such a massive attack against their Führer’s thousand-year Third Reich, who knew what we might go up against? Just prior to the invasion, our ship’s doctor put out word over the bullhorn that in case of a gas attack, he would not issue gas masks to any bearded personnel. A beard would prevent the mask from fitting snugly, rendering it useless. After our doctor’s announcement, even the men who’d had very long beards for years shaved them off. I recall seeing no one on board who still had one after that. Since I didn’t have a beard, however, I didn’t think too much about it. But all of a sudden, guys on the ship would come up to me and start making conversation: “Hello, Mac.” I’d look at them and say, “Who are you?… Eddie! Is that you?” I didn’t even recognize them at first because I had never seen them without a beard. (Thankfully, gas was not used during World War II.)

Just before we were set to get underway for the invasion, while standing on the stern of the Corry, I heard guys on the other seven or eight destroyers that were lined up alongside us calling out to one another and putting money down. They were taking bets as to which destroyer would get sunk first. I took out a ten-dollar bill, waved it, and yelled over, “Hey! I’ve got 10 bucks! Let me in on the pool!” But they all shouted back, “No way! The Corry’s never gonna get sunk! You guys have never had a scratch on you! We won’t waste the bet—the Corry’s too lucky!”

We sailed out of Plymouth,

England, on June 3, due to arrive off the French coast early on June 5 for

the assault. As part of Task Force “U,” the Corry’s destination was

Utah Beach, the farthest of the five invasion beaches. The convoy stretched

behind us for miles beyond the horizon. We traveled at the speed of the

slowest vessels—about 5 knots. Our job was to escort the other ships in

proper formation while leading them to Normandy. We also had to protect them

from enemy attack. Small, fast German torpedo boats, known as E-boats, posed

one definite threat. German aircraft and U-boat attacks were other

possibilities. Mine sweepers forged ahead of us to clear the way. Large

landing craft and other smaller vessels plowed through the water close by,

as did our fellow destroyers USS Fitch (DD-462) and USS Hobson

(DD-464). As we made our way through the choppy waters of the English

Channel, from time to time we’d blink a message over to some of the landing

craft near us, asking them how they were doing. They’d always reply by

flashing the same one-word answer: seasick… seasick….

With the assault on Normandy still more than a day away, we would not be at

full battle stations until we got close to the French coast, unless we had

to engage enemy activity on the way. I spent most of the time checking and

rechecking all of the radar, sonar, and radio equipment. Making the rounds

from department to department, I also made sure that the operators had

everything they needed. Occasionally, I’d step out on deck into the brisk

wind and gaze at the multitude of ships sailing in the convoy.

While en route to France, at

chow time, new guys who had only been on the ship for a month or so were

taken aback: everyone else was sitting down to eat almost as though nothing

unusual was about to take place. Even though the impending invasion was

bigger than anything anyone had ever been involved in and we knew the odds

of making it through were very much against us (the crew had been told by

our captain that we were expendable), the experienced crewmembers were used

to hazardous missions and knew that they would be plenty busy when the

battle started—but until then, they might as well sit down and eat their

food. Afterward, while some of the men kept to themselves, other crewmembers

spent time doing the usual things sailors do: talking, playing cards,

shooting dice. A few took bets on which part of the ship would get hit first

by enemy fire.

The task force continued onward, slowly but steadily making its way across

the Channel. We had endured rough waters and stormy skies for several hours.

Then, as we were getting closer to the French coast, a couple of my radio

operators suddenly received a coded message. It instructed us to delay

operations for 24 hours. We wondered if the message could actually be real,

calling for the abrupt halting of such a massive invasion, but we couldn’t

radio for confirmation because we had to maintain strict radio silence. Only

when the message came in a second time a few minutes later were we convinced

of its validity. Soon, other ships were blinking messages to us, confirming

that they had received the same instructions. We didn’t know why

immediately, but General Eisenhower had, in fact, postponed the invasion of

June 5 because of bad weather. The task force executed a sweeping U-turn and

headed back to England. The Corry, however, quickly sped forward and

circled around the minesweepers ahead of us. We blinked a message to direct

them to turn around and go back. The return trip to England took several

hours, with crewmembers feeling a mix of emotions. We didn’t spend any time

waiting, though; just as we reached England, we received another message to

head out again.

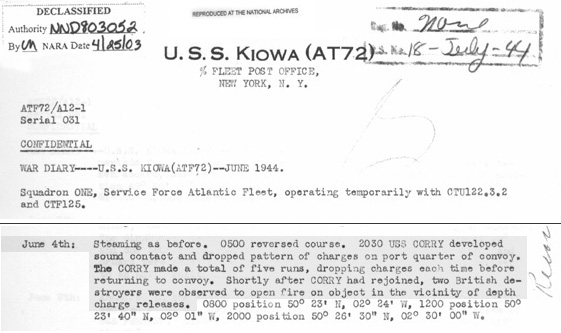

While crossing the English Channel, on sonar we were picking up something—possibly a submarine or maybe it was a sunken wreck on the ocean floor. Since the charts didn’t show a wreck below where we were, the captain didn't want to take any chances. He ordered depth charges to be dropped on it.

Navy tug USS Kiowa (ATF-72) War Diary Excerpt

When the depth charges detonated above the hard ocean floor, the vibrations

from the explosions rattled the ship far more than usual because the Channel

waters were relatively shallow (about 150 feet deep). As a result, some of

the radar equipment malfunctioned, necessitating immediate repair. Radar was

critical to our participation in the naval bombardment. It especially

enabled us to determine the Corry's exact distance to the shore, and with our charts

of Utah Beach we then knew the distance from the shore to each target, which

enabled precise, accurate gunfire.

First, I had to replace vacuum tubes that had blown out when the charges

detonated. Then I got out the voltmeter, ohmmeter, and tube-checking gear

and began running thorough diagnostic tests on all the ship’s equipment. I

had to use dummy antennas that simulated communications as we could not send

out real signals due to strict radio silence. I tried every possible way to

see if I could make the equipment fail. But all of it functioned properly

with every test.

Near midnight,

I dashed up to see the captain, who was sitting on his bunk in his cabin. He

was wearing his best dress blue uniform for the invasion. With voltmeter and

ohmmeter still in my hands, I reported: “Radar, sonar, and radio are all

working perfectly, captain.”

“I can count on that 100 percent, chief? Do you guarantee it?” he asked me.

“Absolutely. I guarantee it.”

That was the answer he was waiting for. Our communications were the critical

eyes and ears we needed in order to continue in the invasion. With the

equipment fully functioning once more, the Corry remained at the lead

and would take part in the naval bombardment in the morning. We would not

have to yield our role to another destroyer. I learned afterward that fire

control and engineering had also experienced problems as a result of the

explosions, and had labored diligently to restore their systems to working

order.

We anchored just a few miles off Utah Beach in the early morning hours of June 6. H-Hour, when troops would land, was set for 0630 a.m. But prior to H-Hour there would be a period of sustained naval bombardment of German shore positions. Prior to that, we had nothing to do but wait for a few hours. The still dark of night was parted by the distant flashes and rumbles made from all the bombs being dropped on the shore by Allied planes. The crew spent the time quietly contemplating what lay ahead. We knew it was going to get awfully dangerous very soon. Shortly before we had left for the invasion, as preparations were being finalized, some of our officers came out of a meeting wearing unmistakably worried looks. They told me and the other chiefs that the charts of Utah Beach they'd been reviewing showed more than 70 artillery batteries, big and small, that could fire on us! The Germans had everything from the relatively smaller 75- and 88-millimeter guns, to bigger 105- and 155-millimeter guns that could cause quite a bit of damage, and even massive 210-millimeter monsters to hit us with. And we were a tin can! (Destroyers were called tin cans because their hulls were very thin.)

For the invasion, I requested and was granted a transfer from the radar room to the bridge. However, on June 6, 1944, Captain George Dewey Hoffman did not have me performing the duties of a radar chief. Rather, with the Corry’s guns making all kinds of thundering noise while blasting away at the shore, my job in the pilot house was to shout out continuous battle reports, man the phones, check our position, and provide anything else the captain and other officers needed.

On the morning of June 6, while maneuvering to our bombardment station, a little after 5:00 a.m. we were fired on by a shore battery. Our fellow destroyer USS Fitch (DD-462), which was proceeding slowly along the shore slightly ahead of us, also came under fire at this time. Though it was before our scheduled time to begin bombardment, a short while later I heard one of our officers inform the captain, “We’re ready.” Immediately Captain Hoffman gave the order, “Commence firing!” I am told that the Fitch and the Corry fired the first shots of the Normandy invasion during this incident.

Once the naval bombardment began in full force a few minutes later, warships continuously provided drenching fire on the shore. Along with the frontline destroyers at Utah Beach [Fitch, Corry, Hobson, Shubrick, Herndon], a few miles to our rear, the battleship USS Nevada and the heavy cruisers USS Quincy and USS Tuscaloosa fired at their designated targets. Several other warships off Utah Beach also bombarded German positions. Every time they fired over us, the Quincy, which was the closest behind us, had a crack to her guns that I'll never forget.

USS Nevada Bombarding

Utah Beach on D-Day

As the action increased, and big ones from the many shore batteries began exploding all around us, erupting towering plumes of water taller than the Corry's mast, to say that we felt “scared” was to put things mildly. Having just led the largest naval invasion in history, we were now on the front lines of the battle of Normandy, and the Germans were trying with all their might to stop us from penetrating their fuehrer’s Atlantic Wall of defense.

For more than an hour, our gunners successfully blasted many German coastal positions while shore batteries tried to close in on us. The batteries would fire one-gun salvos to get our approximate range and then close in with two- and three-gun salvos. Whenever incoming shells would start exploding too close to the ship, the captain would order us to a new position where we'd pursue firing at enemy targets once more. Each time we moved out, we'd quickly change direction to throw off the shore gunners. Turning hard right or hard left, we made several of these abrupt evasive maneuvers during the bombardment. With my back to the rear wall of the pilot house, I'd grab hold of a railing behind me, sliding my arms through it almost down to the elbows to hang on tight as the ship quickly pitched from side to side.

During the battle, the Corry advanced to within a mile of the beach to fire at enemy targets. As we moved in even closer toward the shore, (one report stated that we got as close as 1000 yards), from the bridge I saw quite a bit of the naval bombardment of Utah Beach.

I remember a number of details about the battle:

As our shells exploded all over the shore, spewing smoke, shrapnel, dirt, and rock into the air, I could see German soldiers running and diving for cover all along the beaches.

The Nazis had taken over a Utah Beach hotel for use as one of their observation posts. The Corry’s guns homed in on the hotel and blew it to smithereens—an observation post no more.

Our gunners also scored a direct hit on an enemy communications center camouflaged as a big haystack. Its destruction disrupted German defense activity all along the shore.

German anti-aircraft fire blasted into the skies like the Fourth of July, producing a spectacle of explosions all around our incoming planes. In addition to many Allied bombers flying overhead, I remember the twin-tailed P-38 Lightning fighters zooming by us tight to the water’s surface as they approached the beaches.

During one short lull in the shooting, all of a sudden I heard a roaring Whoosh! Whoosh! Whoosh! Smaller craft had unleashed their deadly rocket launchers at enemy shore positions. Shortly afterward, I noticed several landing craft being led toward the beach by a larger vehicle. Shells were exploding all around the lead craft. I turned away for just a few seconds to check our position. Looking to my right, I got a bearing on the Saint-Vaast lighthouse. When I looked back to where the lead vehicle had been heading, I did a double take. It was gone. It had been blown out of the water that fast.

Some of the land batteries were less fortified, but it was tough to knock out others whose concrete-reinforced housings could take several hits with little damage. Shells had to be landed right inside the small opening where a battery's gun barrels pointed out at sea in order to have any permanent silencing effect.

Not too far from the town of Sainte-Mère-Église, but

closer to the shore, one of the big German artillery batteries that fired on

the Corry sat in the countryside by a village called Saint-Marcouf

(pronounced san mar-KOOF).

The battery was set back from the beach,

a mile and a half inland. I remember well the flames of the Saint-Marcouf

battery's guns, which fired projectiles with a 210-millimeter (8.25-inch)

diameter. They were massive, bigger than those of a heavy cruiser. Today, a sign at the battery says flames shot out more than 50 feet

from the barrels each

time they fired. They were quite noticeable from where we were so close to shore,

and quite scary to witness as within seconds, towering plumes of water would

erupt around the Corry. (This battery is also sometimes called the

Crisbecq battery, as it is located near the hamlet of Crisbecq.)

TWO OF THE

SAINT-MARCOUF

BATTERY'S GUNS

As the Corry’s guns continued firing away at enemy positions, in the pilot house I got a call from below and relayed the message to the ship’s record keeper: “Injection temperature: 54 degrees.” Every day, periodic seawater temperature readings had to be taken so that the boiler crew knew how much to heat the water to keep the machinery functioning properly. “Man alive,” I said when I heard the reading, “someone’s gonna have a cold swim!”

Our gunners fired several hundred rounds of 5-inch ammunition at enemy shore targets. The Corry's gunfire was so loud that men on the starboard side of the bridge could barely be heard by the quartermaster working the charts at the desk on the port side. This is why we needed a person in between to relay information. Not long before H-Hour, I was out on the wing of the bridge, giving my voice a little rest. We took turns shouting out battle reports so our voices would last a little longer. I looked forward and saw my buddy Doc Bresticker, the chief pharmacist mate, come up out of a hatch near the bow. He wanted to take a brief look around and see what kind of action we were in. I waived to him and he gave a quick wave back. Just then a German shell came in and exploded not far from the bow, spewing water into the air, splashing him. Instantaneously, he jumped back below, right down the hatch. I don't remember if he went head first or feet first, but he definitely got out of there like lightning as more shells began exploding close to the ship. When I went back into the bridge, one of my shipmates who was wearing earphones was relaying a message that had come in from below: "One crewmember wounded by shellfire." This was the first casualty I had heard of.

As H-Hour neared (6:30 a.m.), when troops

would land on the beach and the naval bombardment would decrease, while other ships were receiving smoke cover,

we were in trouble. The

plane that was supposed to lay smoke for the Corry got shot down.

With the Corry being the one ship German gunners could see, shells

began to explode closer and closer to us in an increased fury. We were now in a heated artillery duel with

Saint-Marcouf and other batteries.

USS CORRY UNDER CLOSE FIRE

ON D-DAY

At just about H-Hour, one of my radar men, Pete McHugh, came up to the bridge from

the CIC (Combat Information Center). Holding a set of earphones, he said,

"Chief, put these on and use the microphone—we're having trouble hearing

you through the voice tube." I acknowledged what he said but then pointed

out at the water where shells were blowing up all around us. When he turned

to look, he saw a monstrous German shell explode right in front of the bow

of the Corry, spewing a hundred-foot-tall column of water into the

air. He nearly dropped the phones. Pete realized that down in the CIC, he

hadn’t been aware of just how close the Corry was getting to all the

shooting. It was very frightening for us to be in the middle of it all, to

put it mildly; we both knew that when they land them that close, within

seconds, the next three will be right on target—and these were the really

big ones. As Pete headed back below,

with our guns blaring, I shouted in his ear, “Without smoke cover, we can’t

last much longer. When it happens—when we get hit—do the best you can to

take care of the kids!” He nodded his head and left the bridge. The “kids”

were the 17-year-olds and other young guys who hadn’t been in the navy very

long.

Those German gunners now had us perfectly bracketed in their sights and they were real good at what they were doing. With that shell exploding right in front of the bow of the Corry, Captain Hoffman ordered us to move out rapidly from our current position, calling for full speed ahead and then a hard right rudder. As we began to move, immediately, another German shell landed dead on in our wake, skyrocketing a huge plume of water right where we had been.

Then, as we were beginning the hard right turn, with the German gunners still pursuing us, blasting multi-gun salvos at us, suddenly I heard a ripping, tearing sound coming from overhead. Immediately, a jarring explosion ruptured the Corry amidships. Men were thrown from their positions; some ended up in the water; our 5-inch guns all swung around from the jolt; steam hissed and roared violently from behind the bridge—Saint-Marcouf's guns had found us.

In the pilot house, directly in front of me, the captain was thrown out of his chair and flew through the air, pummeling the executive officer, who suffered a severe head wound from the impact. The blast shook the upper parts of the ship so hard that pieces of equipment—the chart desk and ship's helm wheel among them—were ripped out of their base. Everyone was tossed and bounced around violently. But because I was holding on tight during the hard right turn with both my arms threaded through the railing behind me, the severe jolt did not hurl me on the bridge like everyone else; instead, it pulled me backward with my legs going airborne. I tried to hang on, but my arms eventually came loose and I launched into the air. Coming down, I bounced very hard, finally landing on my side. I was still semi-conscious, albeit quite dazed and staggering.

Getting halfway up, trying to maintain my balance, I saw no signs of life around me. Everyone else on the bridge was lying completely motionless, twisted and turned every which way. I slowly crawled my way over to look outside the ship, trying to figure out what had just happened. Out on the wing of the bridge, I could see the 20-millimeter anti-aircraft gunner. Still strapped in at his gun, he was slumped backwards with his eyes closed and arms hanging limp. His support personnel and a signalman were lying near his feet, and they weren’t moving either. In shock, I said to myself, “They’re all dead! I’m the only one left alive!”

(Later I realized that they had all been knocked unconscious.) Then, on my hands and knees, still half dazed, I turned around to look back into the bridge, and suddenly found myself eyeball to eyeball with the captain, who was also on his knees. We stared each other in the face for a brief moment. Then he grabbed hold of me by the shoulders and said, loud and clear, “Chief, listen to me—we’ve lost control of the steering. But we’re still moving! If you’re OK, I want you to go aft, steer north, and get us out of here!”

As I silently took in the order he’d just given, he clenched my shoulders once more, and asked, “What did I just say? Do you understand me?” I nodded my head and answered him, “Yes, sir. Go aft! Steer north! And get us out of here!” He motioned toward the door. “Go!” I got up and ran out of the bridge—heading for the stern, where the ship could be steered manually.

When I got outside on the back of the bridge, steam roared past me so profusely that I could hardly see a thing. I knew that the only source of steam that thick could be a large opening in the main deck. As I was about to descend a ladder to get two levels below, a young seaman emerged out of the steam hurriedly climbing up toward me. Since I couldn't see all the way down to the deck where he had been, I instinctively asked him what kind of damage had been done to the ship. He was so shaken he couldn't even talk—all he could do was blurt out babbling noises as he passed me. I quickly descended the ladder to the main deck. With the wind blowing, some of the steam cleared and I could finally see where I was going.

Near the

foot of the ladder, I came upon a large cracked opening that ran across the

main deck of the

Corry, separating the forward and aft sections of the ship. The crack, about a foot wide, had

smoke and steam pouring out of it. Next to the crack lay one of my

radar men, bleeding pretty badly. I grabbed a passing pharmacist mate and

told him, "Take care of this guy and keep him alive. I gotta go aft!" He

started tending to him.

USS CORRY HIT -

JUNE 6, 1944

I jumped over the crack, careful not to fall into it, and ran past other wounded men who were beginning to get medical attention. Racing along the main deck, I was in too much of a hurry to realize that I was on the side of the ship that was facing the shore—the side the German gunners were still shooting at. In addition to the shore batteries, we were in range of smaller automatic weapons from the beach. However, I arrived safely at the stern. I looked down the manual steering hatch and shouted to the men below, "Captain says steer north and get us out of here!" But the men told me that the blast had caused the rudder to jam, and even one of the strongest guys on the ship—big Jayich—couldn’t get the big steering wheel to move. With the rudder jammed at an angle and the engines still running, all we could do was go around in a circle.

The Germans were still firing at us, closing in on the wounded Corry. From the manual steering hatch, I moved over by the number 4 5-inch Gun to take cover. Suddenly the door to the turret swung open. A shipmate of mine, as he passed a 5-inch shell to me, said, "Here, we have to get rid of these!" I gingerly caught the shell and quickly tossed it overboard. These 5-inch shells were 55 pounds of steel and TNT that could level a house nearly to toothpicks. Getting rid of them was vital; we did not want incoming German ordnance to hit the deadly 5-inch ammunition and blow up the ship.

After only a few minutes, I heard someone shouting from the top of Gun 4, “Prepare to abandon ship!” With a 5-inch shell in my hands, I looked up and said, "Abandon ship? What for?" From where I was near the stern, the ship seemed to be normal—well above the water. Hearing me, my shipmate pointed forward. When I turned to look, I was surprised to see water starting to flood over the deck of the Corry amidships. Its weight was causing the ship to buckle in the middle. I wasn't aware of it, but the heavy-caliber hits we took had broken the ship's keel in the engineering spaces below the forward smokestack. Several men were killed in the area where the shells exploded.

With the Corry starting to jackknife into a “V” I ran back to the manual steering hatch at the stern and yelled to the men below, "Pass the word! Prepare to abandon ship! Prepare to abandon ship! Everybody out!" They climbed up out of the hatch and began making their way onto the deck. While waiting for several of our fellow shipmates to come up from below, we moved forward a little and took cover, crouching down to avoid the incoming German shells.

Our engine rooms now flooding, we began to slow down. All electrical power on the ship had been lost; communications were out, so to indicate that we were in a sinking condition, distress flares were fired from the Corry and a signal was hoisted up the mast: "THIS SHIP NEEDS HELP."

Only a couple of minutes had passed since we'd been told to prepare to abandon. Water was now flooding rapidly over the deck amidships. The bow and stern were starting to point upward at an angle and the Corry's two smokestacks were beginning to lean toward each other. With German shells still landing around us, finally the order came: "Abandon Ship! Abandon Ship!"

Some of my shipmates and I began heading forward along the main deck past Guns 4 and 3 to get to our abandon-ship stations. Above us were crates of 40-millimeter ammunition. Suddenly, we all looked up at the sound of a German shell coming in. A direct hit, it blew up on the upper deck just above us, hurling all of us off our feet. The 40-millimeter rounds instantly exploded into the air like deadly wild fireworks right over us. With the living daylights scared out of us, when we got up, we never ran so fast in all our lives. We were practically running on air.

Heading forward, I looked up at the torpedoes that the Corry carried amidships above the main deck, between the two smokestacks. I could see that something, probably the effects of the big explosion, had caused one of the torpedoes to fire out of its tube and ram into the forward stack in front of it. Luckily the torpedo did not explode; if it had exploded, blowing up itself and the other torpedoes, the Corry would have been demolished.

With our engines now flooded, the Corry drifted in the water and finally stopped moving. The Germans continued firing at us while the ship was sinking. More shells were beginning to explode closer and closer. Naturally crewmembers felt scared with all the nearby explosions, yet the crew maintained very good discipline while getting to their abandon-ship stations. Even some of the youngest guys on the ship were very calm and did exactly what they were told to do with ease.

Near the bridge many wounded were assembled on deck, waiting to be loaded into a whaleboat. One of them, my buddy, and fellow chief petty officer, "Big ’Ski" Rovinski, had burns all over his body from steam that scalded him when a boiler pipe burst below deck. He was in shock. I asked him, “Are they taking care of you?” He said yes. I told him, “I gotta go up a ladder and get my raft.”

When I got near my abandon-ship station, I noticed the raft that had been assigned to me wasn’t there. It had already been cut loose! For the past year and a half I had rehearsed dozens of times how to cut that raft loose in case we had to abandon ship, and now it was gone. I yelled over to a young seaman nearby, “Where’s my raft?” He shouted back, “The other guys thought you were dead, chief, so they took it. They’re out there in the water somewhere.”

Looking forward I saw my buddy Tippy, the chief gunners mate. I yelled over to him and pointed to all the empty 5-inch gunpowder canisters outside Guns 1 and 2. He was thinking the same thing I was; we capped and threw dozens of powder cans overboard. Other crewmembers began doing the same thing. Because these three-foot-long, tube-like canisters were airtight to protect the gunpowder they had carried, they floated and could be used as extra life preservers to help survivors stay afloat. While some of the crew had full Mae West life jackets, many others (including me) had inflatable life belts, which, in the rough waters, might not hold a man quite high enough above the surface. A fellow shipmate, previously transferred off the Corry, had once told me that the best life preserver he knew was a powder canister. He had spent more than 36 hours in the waters of the Pacific holding onto one after his ship had been sunk off Savo Island.

After capping and tossing the powder canisters, I then moved over and helped Doc Bresticker load wounded men into a whaleboat. Some of the able-bodied men gave up their place on whaleboats and rafts to our wounded. Once the whaleboats and rafts had been launched, officers, other chiefs, and I quickly assisted fellow shipmates with their life preservers and helped them off the ship.

Finally, I headed up to the bridge since it was near my abandon-ship station. Only a small number of us, including chiefs and officers, remained on the Corry, the captain among us. Several feet of water now covered the midsection of the Corry. The bow and stern were pointing upward at an angle. I went outside to the back of the bridge, which was normally high above the water level. Others were abandoning the Corry from there. I jumped outward to clear the side of the ship and dropped only a short 15 feet or so before hitting the water. At 54 degrees Fahrenheit, it was bone chilling.

In all the excitement, I made a potentially grave mistake. Just after my feet penetrated the surface, I triggered my life belt while still descending rapidly into the water. The belt inflated instantly, forcing all the wind out of me. I was now several feet below the surface with no air in my lungs. I clawed my way upward toward daylight, almost blacking out. When I finally got to the surface, I took in a huge gasp of air and then breathed several fretful deep breaths in a row. After settling down a bit, I told a shipmate next to me, “I nearly didn’t make it.”

The

captain finally joined us in the water, jumping shortly after the last few

remaining officers and chiefs had. Looking back at the jackknifed Corry,

we saw the stern and bow slanted upward at sharp angles above the water.

Except for the upper bridge and the upper parts of the smokestacks, most all

of the midsection of the Corry was below the surface.

USS CORRY

SINKING ON D-DAY

The stern of the Corry got hit by a German shell, which caused our smoke screen generator’s chemicals to spew out. The wind blew the noxious smoke directly toward survivors in the water, making them desperately ill. The men closest to the stern began to vomit and gag. Some were blinded by the chemicals. When the pungent cloud reached me, its toxic vapors clogged my lungs and made my breathing extremely difficult. It was also quite irritating to my eyes. I frantically tried to swim away as fast as I could, but the current in the water was tough to fight against. Everyone began to scatter over a wide area in an attempt to escape the smoke. There was also oil in the water. Some men caught a mouthful of it. Others got drenched in it. Luckily, I was able to avoid the oil. I grabbed hold of an empty gunpowder canister. Along with my life belt, it helped me stay afloat in the rolling waves.

Away from the ship we were far from safe. The German shore gunners continued to fire relentlessly on Corry survivors, sporadically targeting anyone they could see in the water all morning. They shelled us with both impact-exploding, and anti-personnel ordnance that blew up in the air above survivors. When a shell exploded near enough, it usually killed or wounded someone each time. In an effort to help Corry survivors, some of our warships periodically fired smoke shells past us to temporarily obstruct the view of the German gunners. However, other ships could not leave their bombardment stations to help us during the early critical hours of the invasion, as they had to support the troops now landing on Utah Beach. In addition, they were still being fired on and had large projectiles exploding around them, so trying to swim to them would be much too dangerous. For the most part, the others ships were simply too far away from us. In any event, the rough waves, incoming tide, and strong currents made it difficult to try to leave the area.

At one point, not far from me I saw a shipmate alone in the water who was starting to show signs of panic. I swam to him and gave him my empty powder canister. I told him to hold on to it, kick his feet behind him, and head for a small group of other survivors about a hundred yards away. I knew that his panic could probably be contained if he had others by him, but alone he most certainly would not survive much longer.

After being in the rough, extremely cold water for some time, I made my way to a raft so I could rest for a short while and catch my breath. Several other enlisted men and some officers either sat in the raft or hung onto the side of it. Everyone had been trying to survive as best they could under all the shelling. The shore gunners were still targeting anyone and anything they could spot. After resting briefly, I happened to notice one of my men bobbing in the water. He wasn’t too far from us. Still tired, I somehow felt a strange impulse to leave the raft and help him. I caught my breath and slid back into the cold water. When I got to my shipmate, he was freezing and exhausted, about to drown. I helped him keep his head above water and kicked my feet so both of us would stay afloat. I was with him just a few moments when suddenly from behind me came a whistling sound followed by an earsplitting boom. An antipersonnel shell had blown up directly over the raft I’d just left, killing or wounding everyone on it but one. Lieutenant Bensman was killed instantly when shrapnel hit the back of his head. I remained away from rafts for quite some time afterward.

Troops had been landing on Utah beach for quite a while since H-Hour, battling their way inland in a fury of smoke and gunfire. The main troop landing areas were away from my location in the water. However, a single small landing craft that was heading toward the shore came over and stopped next to me. Its driver offered to take me in to the beach with him. Go in to the beach where everybody’s a prime target—within range of small arms fire as well? I replied, “No thanks. Get me on your way back.”

From time to time, my situation became more and more perilous as antipersonnel ordnance began exploding closer and closer to me, blasting pieces of hot shrapnel downward like a shower of piercing bullets. Floating in the water, there was no place to take cover, so I figured the most I could do was hope that I’d somehow miraculously survive the shrapnel. Then I remembered something. One time back in the Portland, Maine, harbor when we had nothing much to do, I shot at sharks from the deck of the Corry with a .30-'06, the navy’s most powerful rifle. I found out that water puts up more resistance than you might think, and even high-powered bullets don’t go very far in it. The sharks seemed to know this. They’d stay down below six feet or so, just deep enough for my rifle bullets to lose their power. What I learned from those sharks may have saved my life on D-Day. I took off my flotation belt. (Though chilled and fatigued, I was a good swimmer and could do without it for a while.) As I heard an incoming shell, I would take a deep breath and dive down as far as I could. When I heard the exploding shrapnel hit the water above me like a machine gun blast, I would then go back up to the surface for air and wait until I heard another shell coming. The shark trick worked. Several times I was protected from exploding shrapnel above by the thickness of the water. Of course, each time I neared the surface, I faced the possibility of another shell immediately following the one I’d just evaded.

USS CORRY

(LEFT) SINKING - SMOKE SCREEN CHEMICALS

SPEWING FROM STERN. 2nd DESTROYER PASSES

TO REAR AS RESCUE WHALEBOAT APPROACHES

IN FOREGROUND

Eventually, after more than two grueling, bitter hours in the extremely cold water, during which several of my shipmates died or were seriously wounded, I spotted one of our whaleboats with rafts tied in tandem behind it. The whaleboat was overloaded with about 25 men in it, many of them wounded. Because its engine had been wrecked by a German shell before the boat even launched, able-bodied men had to row it with makeshift paddles they'd gotten off the ship. The men rowing were trying to get everyone to the shelter of the Saint-Marcouf islands (about four miles off Utah Beach). As they passed by me, exhausted and freezing, I climbed up on the first raft behind the whaleboat.

Strung together, we were much more noticeable to the Germans, so we had to get to the islands in an efficient, orderly manner—a quick-moving target is harder to hit. But the shells exploding around us were greatly disrupting the rowers' concentration, making it difficult to develop a cadence and keep our movement steady against the current. Seeing some of the men become paralyzed with fear from the nearby deafening explosions, I quickly assisted those who had paddles by calling out to them, repetitively, “St-roke!… St-roke!… St-roke!…” the way a coxswain does for a rowing crew. This helped the men focus their attention, and finally we developed a rhythm and moved more smoothly through the rough waters. As I called out to the rowers, my radioman buddy, Red Brantley, was using his helmet to bail water that was leaking into the whaleboat.

We’d all been through more

than two hours of shelling at this point and were really feeling the strain

of it. Even distant explosions penetrated the nervous system. Each rower was

doing his best to paddle as strongly as he could. I continued to call out to

the men, “St-roke!… St-roke!… St-roke!…” Then, while we were still a ways

from the islands, a German shell suddenly roared in and blew up right next

to us, heaving water over everyone in the whaleboat.

One rower immediately went into a terrible panic. He stood up in the boat and dropped

his paddle, screaming, “We’re all gonna die! Ahhhhh!...”

Knowing that panic can be contagious, I quickly yelled over to my buddy,

“Red! Shut him up!” Red took his metal helmet off and, holding its leather

strap, vigorously swirled it around and clocked the guy on the head with it,

shouting, “Row, you SOB! ROW!!!”

The quick, hard jolt to his head immediately brought the man out of his

panic. He picked up his paddle and began rowing again, German gunners still

pursuing us. Sometimes in a tight situation, tough things have to be done to

pull people through it.

One of my shipmates had

suffered severe internal injuries from being thrown when the ship got hit. I told him we’d be rescued soon, so he just needed to hang

in there a little while longer until help arrived—a few more minutes. I knew

that you should never tell a severely wounded person that help will take a

long time to arrive because just hearing that can cause him to go into shock

and die. After a while, when help was obviously taking longer than I had

told him, he murmured, “Mac, you said only a few more minutes.” I told him

to hang on and said that it should have been only a few more minutes, but a

current in the water was working against us (which it was) so it was taking

a little longer, but help would be here soon. This helped him survive until

we were rescued, but he died later the same morning.

With loud explosions around us, a young kid began screaming hysterically,

totally out of control with fear. I crawled over, grabbed him, and started

slapping him. As my hand made its way back and forth across his face, I

shouted loud and clear, “Shut up! You’re safe! You’re on a raft! Other guys

aren’t! Some are dead!” After my fifth or sixth slap, the kid started

fighting back, grabbing my shirt and trying to get a few wild slaps in at my

face. I interpreted this as a good thing, because his doing so was bringing

him around, getting him out of his hysteria.

Finally, the kid stopped fighting me as he came to his senses. The scared

look on his face drained away as my words sank in. At the same time, he also

realized that he had just been trying to beat up a combat navy chief petty

officer! From his wide eyes and the sheepish grin on his face, I could tell

that he wished he were someplace other than in front of me. Wanting to

assure me that he wouldn’t have done what he did under any other

circumstances, he quickly stretched out his arms, put a bright-eyed kid

smile on, and cried, “Chieeeeef!” Then he gave me a big hug like a

four-year-old greeting his grandpa.

As I patted him on the back a couple of times, I was relieved that he’d come

out of the hysteria. And even though “safe” did not describe our situation,

he now knew that he was still alive and could work with others to help us

get to where we were going instead of causing all kinds of disruption and

possible further panic. There was still a lot of shooting going on around us

and everybody had to stay composed and work together to survive.

As we moved through the water on the raft, I noticed another young kid lying

motionless a few feet away from me. He was so chilled that his face was pale

white. When I moved over to him I could see that his eyes had gone gray—a

clear sign that life was leaving his body. I immediately gave him

mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and slaps, and I shook him to try to get his

circulation going. It took some doing, but eventually I started to see color

come back into his face. When I also saw color and responsiveness come back

into his eyes, I knew that he was going to make it.

With the kid alive and breathing again, I turned away for a few moments as I

caught my breath and regained my composure. When I turned back to check on

him, the kid wasn’t there. I asked a shipmate where he was.

“What kid?” the shipmate asked.

“The kid I just revived!”

Somberly, another survivor replied, “Those nets he was on—they weren’t

secured to the side. He went down to the bottom with the nets.”

“But I just saved that kid! His eyes had gone gray!”

The grief I felt was horrible. I guess he was meant to die sometime on the

morning of June 6, 1944, and there was nothing anyone could do to change it.

The destroyer USS Fitch (DD-462) sent men on one of its whaleboats to help us. They were picking up Corry survivors in the water as they approached. When they got to us, they relieved our overloaded boat of some of its wounded. The Corry’s whaleboat was then tied to the back of the Fitch’s whaleboat. With its putt-putt engine, it started to pull our boat and the rafts.

We were now

close to the Saint-Marcouf islands.

We’d

been told we could go to those islands if the Corry were sunk—Allied troops were

going to take

them during the night. As we made our way through the rough waters, I

could see pillboxes on the nearest island each time my raft rose up with the

crest of a wave. Those pillboxes would provide us with much needed shelter.

When we got within about 200 yards of the

islands, a patrol-torpedo boat, the PT-199, rushed to our aid. They quickly threw a

tow line to

our whaleboat. Several of us climbed up on the PT to relieve overcrowding. We were finally being rescued.

|

|

Patrol-Torpedo Boat PT-199 |

Just as the PT-199 began moving, gunfire erupted from the islands. People were shooting at us! I said to the man at the wheel of the PT boat, “Don’t those guys know we’re friendly?” He answered, “The islands haven’t been taken yet, chief—you’d have been massacred!” The PT-199 intervened just at the last minute, bringing us out of range, over to the USS Fitch. (Later I learned there were also mine fields all over the islands.) PT-199 was commanded by Lieutenant William Liebenow, the same man who had rescued John F. Kennedy in August 1943 after Kennedy's PT-109 was cut in half by a Japanese destroyer.

The PT-199 pulled up along the seaward side of the Fitch. Our fellow destroyer continued firing at the shore the entire time. The big battlewagons behind us were also blasting their huge shells right over us. Wet and freezing, I climbed barefoot up the side of the Fitch.

Patrol Torpedo Boat PT-199 delivers USS Corry survivors to destroyer USS Fitch (DD-462). June 6, 1944. |

Corry survivors climbing aboard destroyer USS Fitch (DD-462) |

On deck I saw our captain greeting his fellow crewmembers. He had been brought to the Fitch not long before we had. I then went straight down below deck where it was much warmer. The men of the Fitch were very helpful to Corry survivors, giving us food, clothing, and blankets, and letting us use their bunks. Even with hot coffee and blankets, I was still shivering for quite a while. Eventually, when I felt a little better, I got up and talked with officers and other enlisted men about our D-Day experience. Everyone was relieved to finally be on board the Fitch. Many of the men were completely exhausted and had severe hypothermia from the extremely cold water temperature. We had endured more than two hours out in the rough, frigid waters under constant enemy fire.

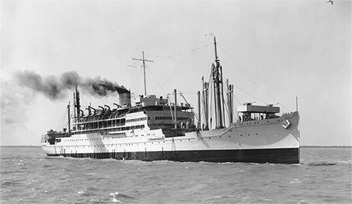

More

than 200 of us stayed aboard the Fitch for a couple of hours or so.

Later on the morning of June 6, we were transferred to an empty

troop transport ship, the USS

Barnett.

USS BARNETT

(APA-5)

For Corry survivors,

the morning of June 6,

1944 was one that none of us would ever forget. At the front of the

battle of Normandy, in all, 24 of our crew had given their lives, and at

least 60 had been wounded, many seriously. We lost more men in the water

from enemy shelling than we did from the ship blast. Some who weren’t

wounded by enemy fire died of exposure to the frigid water. Others drowned.

USS CORRY WRECKAGE

OFF UTAH BEACH

My back had been injured when I was bounced on the bridge, but I didn't notice it much right away—I had so much adrenaline in my system. I also got a piece of shrapnel in my hand; I thought it was just a cut until 15 years later when I had my hand x-rayed after I accidentally hit my finger with a hammer. And the ship's smoke screen chemicals that I breathed in caused me some ongoing respiratory problems. But these were relatively minor compared to what some of my shipmates experienced. Right after D-Day, our captain reported to navy officials how our own smoke chemicals had been harmful to men in the water. Within a year or so, while stationed at the Philadelphia Navy yard, I saw that the top brass had responded to our captain's input by replacing those chemicals with ones that would not pose a hazard to survivors abandoning a sinking ship.

Around midday on June 6, we finally left the French waters of the English Channel aboard the USS Barnett and headed back to southern England. We arrived in Falmouth, England, on June 7 and were taken to the medical facility there. Those of us who weren't in hospital beds stayed only about a day or so. Then we boarded a train and traveled up the west coast of Britain to Rosneath Scotland. Our doctor continued to bandage and rebandage wounded on the train the whole time. In Scotland we spent a couple of weeks at a survivor camp awaiting transportation to the States. Some of the guys picked potatoes in a nearby field for something to do. We played baseball and other sports into the night because the sun in Scotland stayed out quite late during the month of June.

After

the survivor camp, we sailed for New York from the Firth of Clyde on the

liner

Queen Elizabeth. In the States we would be given 30 days survivor leave.

Among those with us on the QE were survivors from other American

warships sunk during the early days of the invasion.

LINER QUEEN ELIZABETH

When we

arrived in New York City, at the pier, a drum and bugle corps greeted us with

patriotic music. Many top navy officials waited there for us, as well as

numerous photographers and reporters. All were eager to see survivors of the

Normandy Invasion back in the States.

Later in 1944, I was offered a commission to become an officer and achieved the rank of ensign following training at Lake Champlain in Plattsburg, New York. In 1946, after being promoted to Lieutenant (junior grade), I was honorably discharged and went back to work in broadcasting as I had done before the war.

EPILOGUE

Well after the war, we learned that it was the big battery at Saint-Marcouf that had hit us amidships with a salvo of two or three monstrous 8.25-inch (210-millimeter) projectiles that detonated in the engineering spaces below the water line, breaking the ship's keel. These details are given in American battle reports and in the book Invasion! They're Coming! by Paul Carell that tells what the Germans were doing on the morning of June 6, 1944. There is also a sign at the Saint-Marcouf battery that says that the battery is responsible for sinking an American destroyer on D-Day. (The Corry was the only U.S. destroyer sunk on D-Day, as well as the U.S. Navy's only major loss that day.)

However, at the survivor camp in Scotland, a couple of weeks after D-Day, just as these gunfire details were about to be submitted as the final official loss of ship report for the Corry, that report was suddenly torn up and a new version was written stating that it was believed that the ship had struck a mine. This contradicted the compiled damage assessment input other chiefs and officers had given that specifically identified enemy shellfire as the cause of the sinking. When it was announced that the ship was now declared sunk by a mine it was quite surprising to the crew, though some just accepted the new version of the loss of the Corry. This abrupt announcement was made just after the captain had returned from a meeting with the commanding officers of the USS Glennon (DD-620) and USS Meredith (DD-726), two destroyers sunk off Utah Beach on June 8-9, 1944, both also declared sunk by mines. (Meredith was hit by a radio-controlled rocket-driven glide bomb fired from a German aircraft, but was officially declared sunk by a mine. See Samuel Eliot Morison's History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, volume 11: The Invasion of France and Germany for details on the glide bomb. My fellow technician Bill Beat's D-Day account gives an excellent description of these glide bombs and the technology used to counter them. Click here to read).

We didn't get to see the wording of the final loss of ship report for the Corry until much later, as it was not declassified for years afterward. As to why the final official records say that the Corry also struck a mine simultaneously with those projectiles that hit us, I could only guess that maybe higher-ups didn't want to admit that the German gunners could shoot so well as to sink an American warship during the invasion.

How we

got sunk doesn't matter so much, however. Simply put, on D-Day—June 6,

1944—we got sunk during a heated artillery duel at the front of the battle

of Normandy, the largest naval invasion in history.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

One interesting anecdote

—

In 1950, when the Korean War started, I went

down to the navy office in Scranton, Pennsylvania, to sign up for active

duty. I talked to a chief who told me that his senior recruiting officer was

on one of the battlewagons off Utah Beach on D-Day. He said that the officer

had watched the Corry still firing her guns after she had begun to

jackknife and take on water. I told the chief that since the Corry

was sinking pretty quickly, amid all the commotion and incoming shellfire, I

hadn’t noticed whether some of the Corry’s guns were still able to

shoot. Then I recalled something. I said to the chief, “I remember having

the daylights scared out of me when the 40-millimeter ammo exploded like

wild fireworks right over my head after a German shell hit it. Could that

have been what the other ships saw firing into the air?” He said, “No. Other

ships saw the Corry’s guns still shooting.” Just then, the recruiting

officer entered the room and informed me that on D-Day he was with his

commanding officer, an admiral, off Utah Beach. They were both watching the

Corry through their binoculars. He told me that when he saw the

Corry in trouble, the admiral exclaimed, “They’ve hit the destroyer

Corry! And she’s still firing her guns as she’s sinking!

That’s the way an American ship goes down!”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

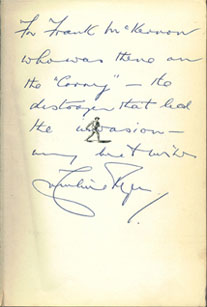

Years later, in 1966, I met Cornelius Ryan,

author of the classic D-Day book, The Longest Day. I asked him if he

would autograph my copy of The Longest Day, which includes detailed

accounts about the Corry, including an entire chapter (7) dedicated

to the USS Corry. He signed my copy of his book, “For Frank McKernon who

was there on the “Corry” – the destroyer that led the invasion – my best

wishes.”

ONE OF SAINT-MARCOUF BATTERY'S GUNS

Francis

“Mac” McKernon

Chief Radio Technician

USS Corry (DD-463)

Cornelius Ryan, Frank McKernon - 1966

WNHC TV Station, New Haven, Connecticut

© 2006 Kevin McKernon