Three 210-millimeter guns (300-pound projectiles, 8.25 inches in diameter).

Projectiles bigger than those fired from heavy cruisers.

THE SINKING OF THE USS CORRY (DD-463)

|

The Saint-Marcouf

(Crisbecq) Battery Three 210-millimeter guns (300-pound projectiles, 8.25 inches in diameter). Projectiles bigger than those fired from heavy cruisers. |

MINE VS. GUNFIRE:

Regarding the Corry's official loss of ship report, which states that the Corry hit a mine:

"We considered that the evidence of gunfire was overwhelming, and none of us had experienced anything that could be taken for the blast of a mine." -- USS Corry officer stationed on the wing of the Corry's bridge on D-Day, commenting on the Corry's battle report suddenly being changed from artillery fire causing the sinking, to a mine stated as the cause. This change in the report utterly disregarded all the damage assessment input from Corry officers, chiefs and crew members. The officer was thrown aft, toward the explosion, and he explains how that motion is consistent with heavy artillery fire hitting the Corry, driving the center of the ship downward, not a mine exploding and driving the center of the ship upward.

The officer also stated: "I have no idea why the official records state that we hit a mine. I personally do not believe we did, and neither did any of the other officers."

Please learn below details of the circumstances under which the Corry's battle report was suddenly changed. Many historians know ONLY the official mine report and quote it as history. They are unaware that from D-Day morning onward, detailed input from the Corry's commanding officer, surviving officers, chiefs and other crewmembers explained how heavy artillery fire had caused the sinking of the Corry. Here you can read and learn what happened to the Corry and how the mine story was not based on any of the detailed damage assessment input. We will expand on this more below, but for now, briefly, after D-Day at a survivor camp in Scotland, a final loss of ship report was about to be submitted by the Corry's commanding officer stating that German artillery had sunk the Corry. However, upon returning from a meeting, (details below) his artillery report was suddenly scrapped and re-written, stating that the Corry had struck a mine. No officers or crew were consulted on the rewrite. All the compiled damage assessment input from officers, chiefs and crew that specifically identified enemy shellfire as the cause of the Corry's sinking was completely disregarded.

THE PROBLEM WITH THE OFFICIAL MINE STORY:

USS Corry survivors have given their detailed input on what happened when the Corry was hit.

Quoting the official report as history: For those who know only the Corry's official loss of ship report which states that the Corry hit a mine and want to maintain that story as history, the first problem to explain is: How does a mine exploding on the seaward side of the Corry amidships (as stated in the official report) cause the Corry to move away from the beach sideways keel first? A mine detonating on the seaward side of the Corry would push the ship toward the beach, not away from it. Heavy artillery hitting the Corry amidships is what pushed the Corry away from the beach when it got hit. The next problem to explain is: How does a mine exploding amidships just above the keel (as stated in the official report) drive the center of the ship downward and cause the bow and stern to rise with men being thrown toward the center of the ship? Incoming heavy artillery shells detonating below the water level drive the center of the ship downward. A mine detonating amidships will not submerge the middle of the ship, and it would not cause the bow and stern to rise when detonating; nor would its explosion amidships throw men toward the center of the ship.

Among many other details of the Corry's sinking, you can read how the report for USS Meredith (DD-726) was also changed from a radio-controlled guided-missile glide bomb causing its sinking to a mine "officially" sinking it, and how the commanding officers of Meredith and Corry attended the same meeting after D-Day, after which the Corry's report was also changed to a mine.

The German Heavy Battery Had the Corry Perfectly Straddled:

"The tightness and regularity of the shell pattern indicated first class gunnery. The shells were perhaps 10 or 15 yards apart, in a neat, straight row." -- USS Corry officer stationed on the wing of the bridge, commenting on the heavy salvo that landed within feet of the Corry bow, just prior to the fatal salvo hit.

"We knew that when they land them that close, within seconds, the next three will be right on target—and these were the really big ones." -- USS Corry Chief Petty Officer stationed on the bridge, commenting on the heavy salvo that landed within feet of the Corry bow, just prior to the fatal salvo hit. The chief was pulled backwards in the pilot house when the Corry was hit amidships; he was not thrown forward.

The German heavy battery had the Corry dead in its sights. Just after the near miss off the Corry's bow, gun flashes of the next salvo were seen and the ripping tearing sound of incoming shells was heard, and then the heavy hit occurred, driving the Corry downward in the water and away from the beach. You'll see below how the commanding officer of the battery was a former chief instructor of artillery for the German Navy.

|

|

The fact that there was a strong concussion effect when the ship was hit was the sole basis for the mine hypothesis on the last page of the final official report. Moreover, on the last page of the official report, the 300-pound heavy-caliber projectiles that exploded amidships (and at the exact same instant as the hypothesized mine), were now officially reduced to having caused "merely incidental damage" to the Corry. Because projectile size details are not given in the official report, anyone reading only the official report is unaware that these heavy artillery shells that hit the Corry amidships measured 8.25-inches in diameter and weighed 300 pounds -- bigger than those fired from heavy cruisers. The projectiles were fired by guns capable of shooting more than 18 miles, and they blasted the Corry at virtually point-blank range. A salvo of these 8.25-inch, 300-pound projectiles does not cause "merely incidental damage" to a tin can destroyer as alluded to in the final report; it causes significant, considerable damage, and produces a substantial concussion effect when detonating below the water level near the keel of a destroyer at very high velocity. |

After the survivor camp meeting attended by the Corry's commanding officer, none of the other Corry officers, chiefs, or crew were consulted for input on the re-written Corry mine report, which then became the final official loss of ship report for the Corry - (click to read).

While initial battle reports and accounts had detailed how heavy artillery projectiles sank the Corry, the new official report, from its front cover onward, stated outright several times that the Corry struck a mine and sank. Only on its very last page does the final report disclose that a mine was believed to have exploded simultaneously with some kind of now unidentified artillery fire. The final official report hides the fact that heavy-caliber projectiles hit the Corry and detonated in the engineering spaces as was clearly detailed in the initial action reports. Further, while all initial input from the commanding officer and crew sited the cause of the sinking to be artillery damage to the port side of the Corry which was the side facing the shore, the damage in the official report was declared to be a mine exploding on the starboard side of the Corry, completely contradicting damage assessment input by Corry officers and crew.

The Heavy Battery at Saint-Marcouf (Crisbecq)

(Pronounced "san mar-KOOF

" and "KRIZ

-beck")

Three 210-millimeter guns

(8.25 inches in diameter, 300-pound

Projectiles).

|

Oberleutnant Walter Ohmsen, |

The battery had a garrison of 400 men. |

The Saint-Marcouf battery, located next to the village of Saint-Marcouf, is also known as the Crisbecq battery, since it is also situated just outside the hamlet of Crisbecq. The Americans tended to call it Crisbecq, and the Europeans called it Saint-Marcouf. Pre-D-Day Intelligence reported six 155-millimeter (6-inch) guns in the battery, but those six guns were moved and three long-range 210-millimeter guns were installed. Located 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers) inland from Utah Beach, the battery reported sinking an American destroyer on D-Day as troops were landing on Utah Beach. The Corry was the only U.S. destroyer sunk on D-Day and the U.S. Navy's only major loss that day. (Initiall Saint Marcouf believed the Corry to be a light cruiser.)

|

210 mm Skoda K39/K41 Gun (Czech made) Shell Diameter: 8.267 inches (210 mm) Shell Length: 2.62 feet, or 31-1/2 inches long (80 cm) Shell Weight: 300 pounds (135 kilos) Shell loading/firing capacity: every 40 seconds Range: 18.5 miles (30 kilometers) Source: Saint Marcouf Battery Museum |

Note that some accounts say that a fourth gun of lesser caliber from a nearby battery may have been firing in unison with St. Marcouf/Crisbecq's three guns. This would explain accounts that describe salvos of four shell splashes being seen near the Corry.

DETAILS BELOW ABOUT THE SINKING OF THE USS CORRY:

Read the initial reports on the sinking of the Corry where heavy artillery hit the Corry.

Read the German battle reports from D-Day telling how St. Marcouf battery caused the sinking.

And listen to the June 9, 1944 Edward R. Murrow interview of the Corry's commanding officer, which completely contradicts the official report in detail.

Read below details on the sinking from first-hand D-Day accounts by Corry survivors.

And read especially the section below on the physics of the explosion -- which are completely the opposite of what a mine would cause.

Read how the report for USS Meredith (DD-726) was also changed from a guided-missile glide bomb causing its sinking to a mine "officially" sinking it, and how the commanding officers of Meredith and Corry attended the same meeting after D-Day, after which the Corry's report was also changed to a mine.

INITIAL USS CORRY D-DAY REPORTS AND ACCOUNTS:

Initial USS Corry action reports (click here to read) and accounts of the sinking of the Corry stated that the loss of the ship was due to a salvo of heavy-caliber projectiles that hit the Corry amidships below the water level and broke the ship's keel at about H-Hour (6:30 am). These reports identify and detail what kind of projectiles detonated, and where they detonated, and the damage they caused -- projectiles entered below the water level in the forward fire room and forward engine room which are aft of the bridge area below the forward smoke stack and the ship's torpedoes.

Additionally, the Corry's commanding officer, in a June 9, 1944 CBS radio interview with Edward R. Murrow (click here to read / listen), gives a detailed description of how "three large projectiles entered almost simultaneously." That is quite a different account from a mine exploding amidships.

Also, D-Day newsreels and NBC radio broadcast all report the Corry being sunk by artillery fire, as do several D-Day reports from other vessels -- no mention of a mine exploding on the seaward side of the Corry. Those who observed the Corry in action saw it get hit by artillery. Several action reports of nearby ships and vessels, and first-hand accounts of personnel tell of witnessing the Corry being sunk by shore battery fire.

GERMAN D-DAY REPORTS: St. Marcouf Battery sank the Corry

German battle reports also agree with the initial American reports and accounts: The American report states that Corry was hit at 06:33 a.m. on D-Day; the War Diary of the German Sea Commander has its log entry for 6:35 a.m. stating that direct heavy caliber hits from the German heavy battery at Saint-Marcouf (a.k.a. Crisbecq), which fired 300-pound projectiles struck the warship that was the Corry. (The Corry was the only US warship sunk on D-Day) The commanding officer of the Saint-Marcouf battery, Walter Ohmsen, was the former chief instructor for the German naval artillery school at Sassnitz, a top rate expert artillery marksman. First-hand input given by Corry survivors tells how he had straddled the Corry perfectly with salvos leading up to the final fatal hit.

Click here to view the German D-Day reports

with English translations.

Click here to view the German D-Day reports

with English translations.

Further, one Corry survivor, the Gun 3 gun captain, described how the explosion caused the ship to be driven sideways away from the beach, keel first, with the ship's upper superstructure moving downward toward the shore. Such movements are consistent with heavy artillery projectiles hitting the Corry on the shore side below the water level at point-blank range, driving the ship away from the shore. The official report states that a mine exploded on the Corry's starboard side, which was the seaward side. Such a mine explosion would drive the ship toward the shore, not away from it.

Another survivor, a 40-mm gun crewman, who was stationed aft of the explosion area was outside on the upper deck of the Corry by the ship's second smokestack -- he explained how he was thrown upward into the air by the jolt when the ship got hit. After rising into the air, just as he began to come down, the ship rose back up and hit him. These physical movements are consistent with the middle of the ship being driven down into the water when it got hit, where the great extra volume of air below deck not normally beneath the water level would then cause the ship to launch abruptly back upward out of the water and hit the crewman while he was still in the air. (Ensign Beeman gave the analogy of pressing down on a toy boat and then quickly letting go: the boat will quickly pop up out of the water due to extra air below the water level.)

THE CORRY'S BATTLE REPORT WAS CHANGED

After D-Day, at a survivor camp in Scotland the report that detailed how heavy enemy artillery fire had sunk the Corry was about to be submitted by the commanding officer as the official loss of ship report for the Corry. However, after a meeting of the surviving commanding officers of the USS Corry, USS Meredith (DD-726), and USS Glennon (DD-620) took place, the Corry's battle report was suddenly discarded and a new contradictory report was written up by the Corry's commanding officer, stating that the Corry had struck a mine on D-Day. (The Meredith and Glennon were also declared sunk by mines off Utah Beach following the survivor camp meeting -- see below for details on how the USS Meredith was not sunk by a mine on June 8, 1944 but was officially declared to have struck one.) (Meredith was hit by a German rocket-powered, radio-controlled guided missile glide bomb fired from a He-177 aircraft.)

One Corry officer stated that the tightness and regularity of the shell splashes around the Corry just before the big hit "indicated first class gunnery. The shells were perhaps 10 or 15 yards apart, in a neat, straight row." His statement is consistent with the fact that the commanding officer of the St. Marcouf battery was a former chief instructor of the German naval artillery school at Sassnitz, Germany, making him a top-rate gunnery expert. In addressing the change to the Corry's battle report from artillery fire to a mine, the Corry officer stated, "We considered that the evidence of gunfire was overwhelming, and none of us had experienced anything that could be taken for the blast of a mine."

As to why the final official report stated a mine caused the sinking of the Corry, some speculate that Allied Command may have ordered the change because they wanted to discredit the marksmanship of the German gunners in the invasion. That the USS Meredith's report was also changed to a mine after a meeting of the commanding officers of the Corry, Meredith, and Glennon, gives credence to contradiction between actual battle activity and "officially reported" activity for the Corry.

In any event, with first-hand input from survivors, noting the direction men were thrown on the ship, and that the Corry was pushed away from the beach keel first when it was hit, a mine could not have exploded on the seaward side of the USS Corry as is reported in the final official report.

Some crewmembers have stated that the Corry hit a mine largely because that is what they were told happened after the sinking. While unfortunately, the final official report is usually what is considered history, again, the USS Meredith's official report of a mine sinking the Meredith is not true.

All in all, however, Corry survivors are not so much concerned with how the USS Corry was sunk. For them, the fact the USS Corry was sunk on the front lines on D-Day while blasting enemy positions and attempting to eliminate the heaviest artillery battery on the shore during the invasion to break Adolf Hitler, is what is important.

For specific details about mine vs. gunfire, read D-Day accounts of Corry survivors Ensign Robert Beeman and Chief Petty Officer Francis "Mac" McKernon on the D-Day accounts page.

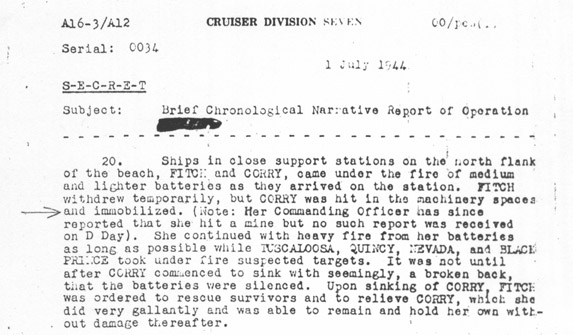

| BELOW: Cruiser Division 7 battle summary noting changed report for the loss of the USS Corry |

|

Note above: Pre-D-Day Intelligence reported six 155-millimeter (6-inch) guns in the Saint Marcouf battery, but those guns were moved elsewhere before D-Day and three heavy, long-range, 210-millimeter (8.25-inch) guns were installed. |

|

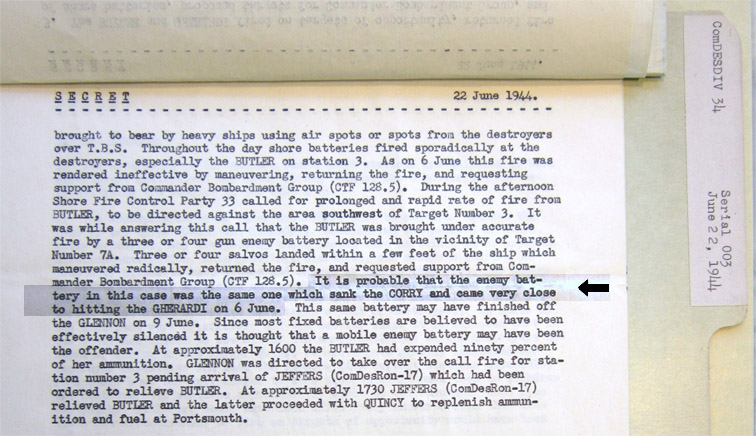

BELOW: COMDESDIV 34 REPORT

ACKNOWLEDGING USS CORRY SUNK BY SHORE BATTERY FIRE BELOW: June 7, 1944 entry of COMDESDIV 34 Report acknowledging USS Corry sunk by artillery fire.  |

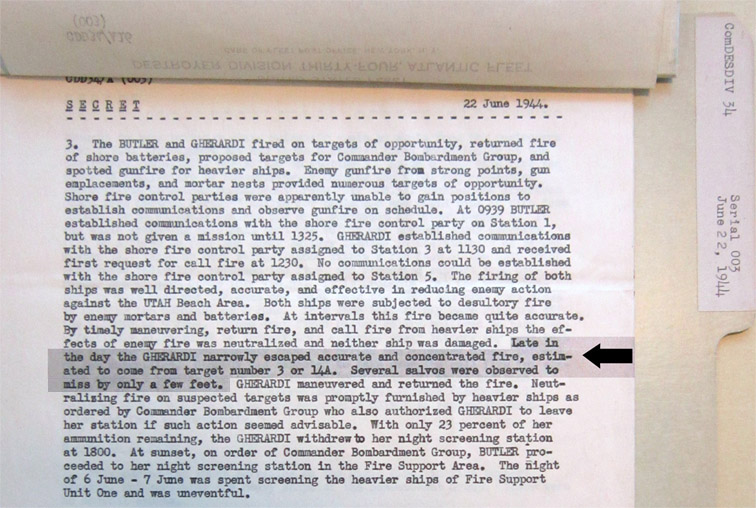

BELOW: June 6, 1944 entry indicating USS Gherardi under

fire from vicinity of Target 3 (St. Marcouf/Crisbecq battery)  Above reports declassified NARA. |

|

|

Read about the concussion effect of a salvo of heavy caliber projectiles.

|

|

|

SAINT-MARCOUF : THE

CRISBECQ BATTERY The only heavy battery on the eastern coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, the Crisbecq Battery, was located 2.5 kilometers from the shore on a crest overlooking all of Utah Beach. From Crisbecq, the Germans could see and defend the entire coastline from Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue to Grandcamp. Although it was never completed, the Crisbecq battery was the keystone of this portion of the German Atlantic Wall with three, long-range 210 mm cannons and a garrison of 400 men. The Allies dropped over 800 bombs on Crisbecq between April 19 and June 6, 1944. This unrelenting aerial attack climaxed on the night of June 5 when 101 four-engine bombers unleashed 598 tons of explosives on the battery. On June 6, the surroundings were unrecognizable, but the guns were still intact. At 6 am on D-Day, as GI’s were landing on Utah Beach, Crisbecq opened fire, sinking an American destroyer. The battery held out for several days, despite shelling by U.S. battleships and attacks from the American Infantry in hand-to-hand trench combat. To repel the Allied assault, the German commander of Crisbecq radioed to the Azeville battery and requested that it fire on his position. Crisbecq was finally taken at 8:20 am on June 12, after the German commandment ordered its troops to evacuate to La Pernelle, between Quettehou and Barfleur. The fierce German resistance momentarily halted the Allied Advance to the north. |

MORE PHOTOS

One of Saint-Marcouf's three 210-millimeter (8.25-inch) guns

June 21, 1944

Two concrete-reinforced casemates

of the Saint-Marcouf (Crisbecq) battery.

Fifty-foot flames spewed from the

gun barrels when they fired.

The battery's third 210-mm gun was free-standing outside with no

casemate housing.

View toward Utah Beach from Saint-Marcouf

(Crisbecq) battery. 1944

(Houses along the beach, 1.5 miles distant from the battery.)

[National Archives photos]

Modern Look Saint-Marcouf (Crisbecq) Battery (2004)

With a garrison of 400 men, the Crisbecq (Saint Marcouf) battery was one of

the most important on the East Contentin coast. The position contained two 210-mm (8.25 in.) guns in casemates, one 210-mm in an open emplacement, and six 88-mm dual purpose guns in open emplacements. The casemates had roofs of

reinforced concrete 12-1/2 feet thick and walls ranging from 10 to 16 feet thick. One of the three 210-mm guns was destroyed on D-Day by a direct

heavy-caliber hit. All the other guns in the battery which were not

enclosed were eventually destroyed or nearly so. There were ample bomb-proof personnel

shelters in the area which afforded complete protection to the gun crews. In

2004 the entire site was excavated. It is now a museum.

Destroyed Saint-Marcouf encasement. Roof nearly 13-feet thick collapsed when demolition engineers destroyed it after capture. |

Close-up view of destroyed Saint-Marcouf battery encasement. |

|

|

|

|

|

Inside battery's bomb-proof personnel shelter. |

Fragmentation scars at Saint-Marcouf battery.

[Photos: S. Voskuil,

The Netherlands, 2004]

|

View Maps and Reports of Utah Beach Enemy Batteries / Targets including Saint-Marcouf / Crisbecq |

|

|

FULL USS CORRY

LOSS OF SHIP REPORT AND D-DAY ACTION REPORT - View as Text or Images View Full Corry Loss of Ship / Action Report - Text - (Loads Quickly) View Full Corry Loss of Ship / Action Report - 13 Scanned Images |

Contact: webmaster @ uss-corry-dd463.com