Corporal - 1937

PA National Guard

2nd Class Petty Officer

1942

1st Class Petty Officer

1943

Chief Petty Officer

1943

USS Corry (DD-463)

Shipmates

Francis "Mac" McKernon

|

Francis McKernon in 2003 at the US Navy Memorial Lone Sailor statue, West Haven, Connecticut beach. |

|

Born in 1917 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, Francis "Mac" McKernon enlisted with the U.S. Naval Reserves in March 1942. He spent most of that year in top secret technical training at two Navy communications schools, one in Grove City, Pennsylvania for 12 weeks, and the other at the Bellevue Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC for 24 weeks. Prior to the navy, he served for six years as an infantry radioman in the Pennsylvania National Guard from 1934 to 1940, where he reached the rank of staff sergeant. After his extensive navy electronics training, Mac reported for duty aboard the USS Corry on January 5, 1943 as a petty officer, first class. In November 1943, he became a chief petty officer. As chief radio technician, he was responsible for all radar, sonar and radio operations and repair for the entire ship. He served aboard the Corry until the sinking on June 6, 1944, a total of 17 months. Following the loss of the Corry and 30 days survivor leave in the U.S., he served aboard the light cruiser USS Wilkes-Barre (CL-103) for two months until being offered a commission to become an officer. In November 1944, upon completion of officer school at Lake Champlain, NY, he became an ensign and was stationed at the Philadelphia navy yard where he served as training and equipment officer. In 1946 he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant, junior grade. In April of that year, he was honorably discharged from the navy, and went back to a civilian broadcasting career.

Francis McKernon

passed away peacefully at home on December 9, 2003 at the age of 86. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

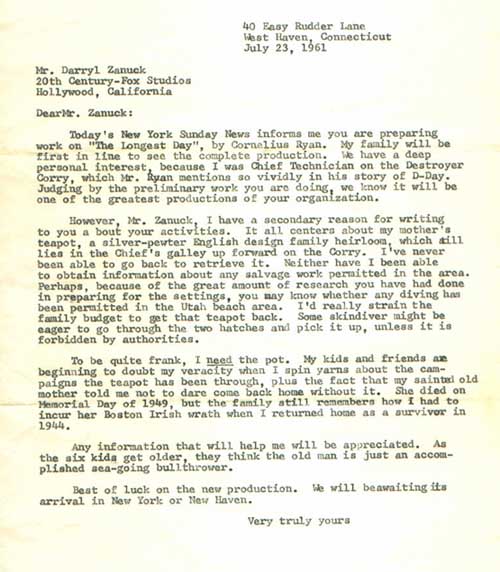

Darryl Zanuck forwarded my letter to Cornelius Ryan, author of the book The Longest Day, on which the film is based, who warmly replied: (below) (letter partially damaged) |

|

COMING TO THE CORRY - MAC McKERNONRadio always fascinated me. While some kids just listened to a radio, by age 13 I was building my own miniature radio sets, learning everything there was to know about how a receiver worked. By the time I was 15, I had learned Morse code on my own and was using it to communicate with members of a local radio club. I knew from then on that I wanted a future in communications. Shortly after high school, in 1934, I became an infantry radioman with the Pennsylvania National Guard in Scranton, where I served as a part-time soldier for six years. In 1936, while still a teenager, I obtained my commercial broadcaster’s license and began working full-time as a radio broadcast engineer. All of this experience prepared me well for the job I would later do on the Corry.After Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, as I saw the conflict escalating in Europe, I knew that war would eventually be a strong possibility for the United States. Since the mid-1930s, I had listened to Hitler’s speeches on shortwave radio, hearing interpreters translate and summarize them. Some of the outrageous things Hitler was saying made me uneasy, and I needed no interpreter to sense the fury in Hitler’s voice. Though trying to keep the United States out of the war in Europe, President Roosevelt instituted a peacetime military draft as a precautionary measure in 1940. After I was discharged from the National Guard that year, because I had been taking care of elderly parents, I was exempt from the draft. And when I got married in June of 1941, I became doubly exempt. Nevertheless, I was willing to serve again if a major threat should arise. With the attack on Pearl Harbor thrusting the United States into war against Japan, and with Hitler declaring war on the United States right afterward, I knew I would soon be putting on a military uniform again. After reviewing enlistment options open to me, I began talking with recruiters from the U.S. Naval Reserves. They were enthusiastic about my background in military radio, ham radio, broadcast engineering, and electronics. Also of great interest to them was the fact that while in the National Guard, as a staff sergeant, I had qualified to become an officer. I had taken and passed all the tests for the rank of army lieutenant, and the Guard offered me that rank, though I did not re-enlist to gain the promotion. In early 1942, I enlisted with the Naval Reserves when they offered to make me a radar, sonar, radio, and electronics specialist—everything I’d wanted and more. I knew that, with the high-tech military occupation they were giving me, I’d most likely be serving on active duty for quite a while unless the war were to come to a quick halt somehow. In 1942 I went through several months of full-time technical training. The Allied technology was top secret—our radar was far superior to what the Germans had. While being trained, as well as afterward, I could never mention anything about radar or sonar outside a ship or military base. I was always simply known as a radio technician or someone who worked in communications. In the first week of January 1943, I was assigned to

active duty on the destroyer USS

Corry (DD-463). I came on board as a first class petty officer.

Later that year, I became a chief petty officer. As chief radio technician,

I had 48 men reporting to me. Except for me and one other technician who

maintained and repaired all the equipment, the rest were mostly radar,

sonar, and radio operators, but also included were the Corry's signalmen and

a few communications yeomen who performed our clerical duties. At the ship’s

radio, I was always aware of what we were up to. Working with radar and

sonar, I knew of any activity in our vicinity. And at Normandy, less than

one mile off Utah Beach, my battle station was on the bridge of the

Corry, so I saw plenty

of the naval bombardment action—until we got sunk. |

BEFORE THE CORRY - NAVY HIGH-TECH TRAINING

Navy College at Grove City,

Pennsylvania - June 1942

Communications training for radar, sonar, and radio.

McKernon - Grove City, PA - June 1942

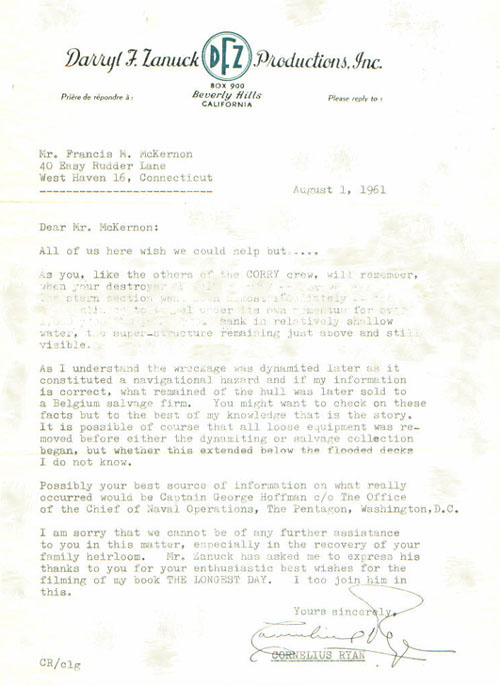

Sailors and Marines -

McKernon: kneeling behind Fido. June 1942

Grove City, PA

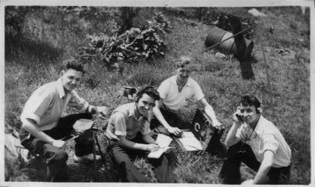

McKernon: 2nd from Left July 1942

Grove City, PA

Sailors and Marines between

classes July

1942

Grove City, PA

Sailors lashing hammocks July 1942

Grove City, PA

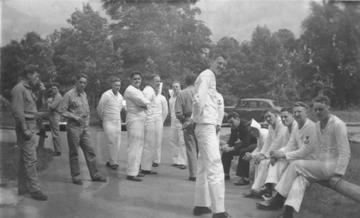

Grove City, Pennsylvania Navy

Communications Class

McKernon: 2nd row, 2nd from left.

Attended for 12 weeks from April to July 1942 for prerequisite math and

electronics courses.

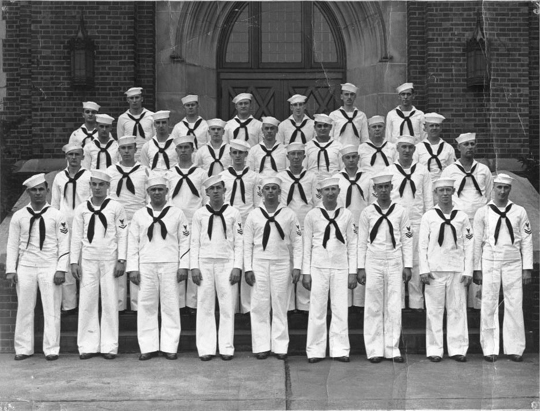

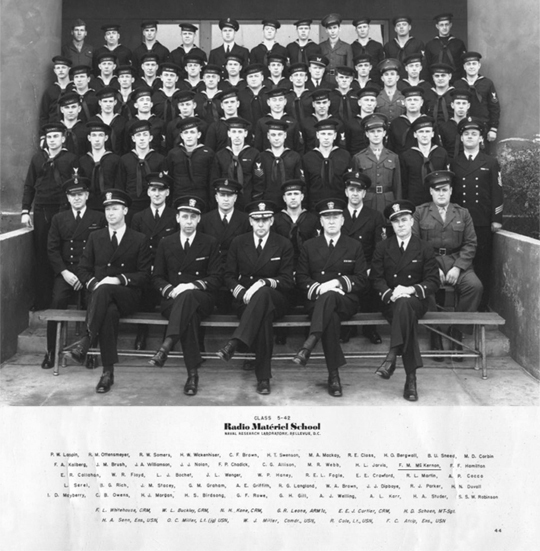

Bellevue Naval Research Laboratory Class - Washington, DC

McKernon: 2nd row from top, 2nd from right.

Attended 24 weeks from July through December 1942 for radar, sonar, and

radio operations and repair training.

AFTER THE CORRY -

|

Following 30 days survivor leave in July 1944, spent two months aboard the new light cruiser USS Wilkes-Barre (CL-103) for shakedown duties in the Caribbean. While aboard the Wilkes-Barre was offered a commission to become an officer and left to attend officer school at Lake Champlain in Plattsburg, NY. Upon completion of officer school, was stationed at the Philadelphia Navy Yard at the electronics base lab and huge equipment warehouse until discharge in 1946. |

Ensign F. M. McKernon with wife Fran

and daughter Mary Ann. Feb. 1945

Ensign F. M. McKernon with wife Fran after snowfall. Feb. 1945

BEFORE THE NAVY - PENNSYLVANIA

NATIONAL GUARD

Pennsylvania National Guard radio buddies - 1936

Pennsylvania National Guard buddies - 1938